I had my first midlife crisis in 2006. It started at 7am on a cold January morning when my mother got out of bed, made herself a cup of tea, had an aneurysm and died.

I was a 46-year-old married newspaper columnist with four children, who appeared to be living a more than satisfactory life. But as the sudden axe of grief fell, I looked at my career, which was going better than I’d ever thought possible, and thought: I don’t want this any more.

Mum had been a brilliant teacher at Camden School for Girls (where I also went in the 1970s), and even though the idea of teaching had always seemed horrible to me (too much work, too little money, no glamour, no recognition, really nothing to recommend it at all) I started to research postgraduate certificate in education (PGCE) courses. I was greeted by the smiling faces of 22-year-old trainees and thought: damn, I’ve left it too late. So I banished teaching from my mind and went back to doing what I had already been doing for 20 years: writing sarky columns and interviews for the Financial Times.

My next crisis, the one that brought the whole thing crashing down, happened 10 years later. This time it was my father’s death that started it.

In the raw days after Dad’s funeral I once again found myself Googling PGCE courses and was again greeted by pictures of twentysomething teachers. This time, instead of thinking I was too old, I thought: I don’t care, I’m doing it anyway. A couple of months later, I marched into the FT editor’s office and told him I was leaving to be a maths teacher – and setting up a charity to encourage other people my age to do the same thing.

“You sure about that?” he asked.

“Yes,” I said.

When I told people what I was planning to do, they all either said I was mad or (which amounted to the same thing) brave. But jacking in journalism to become a teacher so late in life wasn’t brave – it was desperate. Though I didn’t admit it at the time, I was entirely burnt out – I had been at the same place for an interminably unimaginative 32 years – and was showing the classic symptoms. I was cynical about the value of what I did and of journalism as a whole – what was all this crazy chasing of ephemera really for? I also felt the columns I was writing were rubbish. The very thought of writing another one was making me feel so sick I had to find a way out and do something else entirely.

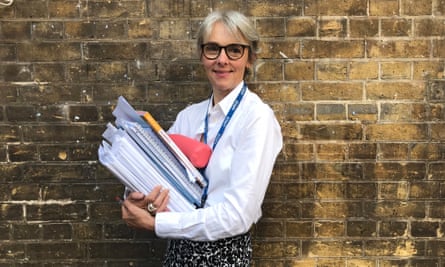

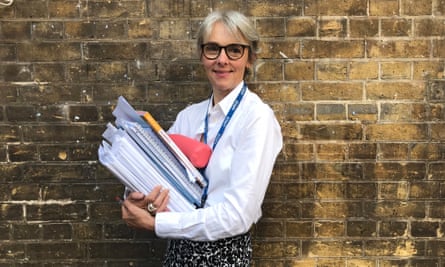

View image in fullscreenLucy Kellaway, carrying a pile of marking at school.

View image in fullscreenLucy Kellaway, carrying a pile of marking at school.

Secondly, there was little financial sacrifice in quitting. Even though my new salary as a trainee would be barely a fifth of my old one, I owned my house and had savings as I had never spent anything like the money I earned. I also had a pension that would start in five years’ time.

It would have been much braver (and much madder) for me to quit at 47 when my children were all at school and required a certain amount of policing, feeding, homework assistance and financial support. Back then, I was still in thrall to the status of what I did (though at the time I would have denied that). The Financial Times was part of my identity – it was the impressive part. I feared that without it people wouldn’t want to know me any more. I wouldn’t be asked to things. There would be no more invitations to the champagne opening evening of the Chelsea flower show. Ten years on, the appeal of status had worn very thin – I knew my close friends would still like me if I was a teacher, and if I wanted to go to the Chelsea flower show that badly I could always buy my own ticket.

In the end, leaving wasn’t hard. There was almost no jeopardy. The only risk was one I had manufactured myself: having set up a charity to lure others into the classroom, I couldn’t leave if I didn’t like it. “Can’t wait to read about her quitting teaching in a year’s time saying it’s too hard,” a reader commented underneath an article I had written explaining what I was doing. That wasn’t going to happen, I cheerfully told myself, because I was going to love it. I am a natural showoff and I had teaching in the blood. My age and confidence would surely help – the kids would look at my grey hair and assume I had been doing it all my life.

This was not a view shared by my 24-year-old mentor in one of the Hackney comprehensives I trained in. When he was told he would be mentoring someone of 58 his heart sank. It sank still further when he Googled me and found evidence of a big-ego columnist who would shortly be swanning into his classroom, thinking she knew it all. How’s that going to work, he wondered. Later, when he sat at the back of his classroom and watched me fail to get my slides up on the smart board, handing out the wrong sheets, mispronouncing students’ names and getting so flustered that I ended up teaching a class of low-ability 11-year-olds that minus six times minus eight is minus 48, it was even worse than he had feared. He simply thought, Jesus.

I have forgotten the pain of my training year in much the way I’ve forgotten the pain of childbirth. But even though it was brutal, I never once wished to be back in my familiar old life. Instead, I was in the middle of something that was thrilling and excruciating in equal measure. I was in an altered state, waking at 3am wired and with the faces of my students filling my head. I was obsessed with what I was doing – the last time I had felt so single-minded about anything was when I was in the first flings of love.

Four years in, I’m still teaching at the same academy chain in Hackney, east London, but have switched from maths to economics, which I have a degree in and am rather better at. These days I’m taking it more in my stride, and though I am still too scatty and careless to be the great teacher I want to be, I am good enough to be able to answer honestly when people ask: “Do you love teaching?” The answer is yes.

View image in fullscreenLucy Kellaway at her school in east London. Photograph: Anna Gordon/The Guardian

View image in fullscreenLucy Kellaway at her school in east London. Photograph: Anna Gordon/The Guardian

I was teaching an economics class about inflation the other day and a student put up her hand and asked: “Miss, does the existence of inflation prove that capitalism doesn’t work?” I gave an inadequate, off-the-cuff answer about how some inflation helps capitalist producers, but then had to move to the next stage of the curriculum. Back in the staffroom I admiringly repeated this to my colleagues, adding: “I bloody love this job. The students make me think about economics more deeply than my university professors ever did.” On hearing this, one of my young teacher friends piped up: “Don’t you wish you’d become a teacher earlier?” What I think she was saying was: given your age (I am the oldest person in my school by two decades) you won’t be able to go on for much longer.

I put the question back to her and asked how many more years she thought she’d teach for. “Not sure,” she said. “Maybe another five. Then I want to do something less exhausting.” Well, in that case, I replied, I’d be at it for much longer, as I plan to teach until I’m 75. She looked at me sceptically. Partly it was my bravado talking, though if my health holds out, I don’t see why I shouldn’t.

I don’t wish I had switched careers earlier. But what I do wish is that someone had told me long ago that my working life would probably last at least 50 years, and I would need to have multiple careers. I wish the government and employers were thinking about this, too, and helping us along. I wish that everyone was taught at the outset that it was normal for their income to rise and fall precipitously over their working lives, and to plan for that. I wish that my story was so commonplace that there would be no point in my writing it.

Instead, it took a decade and two parental deaths to make me confront something that was staring me in the face. It is the same thing that is staring all of us in the face. We need to think about how many decades we really want to be retired for. When pensions were introduced in 1908, three-quarters of the workforce were dead before they received one. Now, the average person who draws a pension at 66 can expect 20 long years of retirement, longer if you are a woman, healthy and live in a more affluent part of the country. The actuaries tell me that I will live until I’m 93 – which means another 31 years of life, the majority of which I would like to fill with some diverting work.

I wish that my story was so commonplace that there would be no point in my writing it

My generation was brought up to think that we would do one thing and when we had made enough money or got tired of it, we would stop working altogether. Some of my professional contemporaries have started building portfolio existences and do a bit of this and a bit of that, but the more obvious route – an entirely new career – is still a rarity. This is not because people don’t want to start again, but because no one is showing them how.

When we launched Now Teach in 2016 we were hoping to find a dozen ageing weirdos like me for a pilot programme. Instead, we had 1,000 applications in the first couple of weeks. At first, I was jubilant, though on closer inspection it turned out that many were less interested in teaching per se than in anything that would mean a fresh start doing something useful. The first application to arrive looked great on paper – a first in chemistry from Cambridge, a long, successful career in management. Only the next day he emailed to withdraw it: he had discussed the plan to teach with his wife over supper, and she had pointed out that he didn’t like children very much. That first year we found 45 people who were determined to teach, and since then have recruited a total of 500 people and slotted them into existing teacher-training programmes, most of them based in schools where they learn on the job. Though I’m proud of this, I’m also aware it’s a modest molehill compared with the mountain of ageing, rootless talent out there looking for a useful occupation.

You don’t need to be an economics teacher to see that the nation is simply not using its resources properly. I’m hoping to see copycat schemes springing up for nurses and police officers (and perhaps one for clerics that could be called Now Preach). They don’t even need to be in socially useful occupations – it would be good to see schemes for people in midlife to retrain at anything at all.

This week, someone tweeted: “I’m a burnt-out 50-year-old teacher. Where is the scheme to become a journalist?” Indeed! Where the hell is it? A few years before I left, the FT hired a fiftysomething former hedge fund manager whose progress I watched with interest. Even though he didn’t know how to write (he learned fast) there was a lightness and ease about him that was very different from the graduate trainees. Now I understand why.

Starting again turns out to be much easier, less stressful and less scary than starting out the first time. I often compare myself with my young teacher colleagues. It has occurred to me that I like my job more than they do, and I’m much less dragged down by it all. The reason is obvious: they need to climb the ladder, to make more money and to impress their managers. I don’t need to do any of these things.

As long as my managers don’t think I’m such a liability that they camp out in the back of my classroom, it doesn’t matter if they don’t like me very much. I would slightly rather they did, but I don’t need their support for promotion, as the very idea is abhorrent to me: I am actively avoiding extra responsibilities, which inevitably come with more stress and a lot more spreadsheets. For the first time in my life, I am trying to do the job well for its own sake, and for the sake of my students.

View image in fullscreenLucy Kellaway teaching economics. Photograph: Anna Gordon/The Guardian

View image in fullscreenLucy Kellaway teaching economics. Photograph: Anna Gordon/The Guardian

There is a further release in no longer having to prove myself. I did that long ago by being a decent columnist – now, if I give a bad lesson, I don’t conclude that I’m an all-round wretched person; I merely think about how to do it better. My ego isn’t on the line in the way it once was. This means I’m easier on myself than most twentysomething teachers. All of us work prodigiously hard, but I refuse to work in a way that is not sustainable. The job of a teacher is never done, but because I’m older I have the confidence to know which tasks to concentrate on and which to skip. If I have been working for 10 hours with no proper break for lunch, I simply stop and go home. And if my colleagues are still bent over their marking, I tell them to follow me as I pick up my things and leave. If I’m going to last until I’m 75, I’m not getting burnt out again.

Re-educated: How I Changed My Job, My Home, My Husband and My Hair by Lucy Kellaway is published by Ebury (£16.99).