Just over a decade ago, Peter Singer issued a fundamental challenge to the relatively wealthy world. In The Life You Can Save, the Australian philosopher argued that most of us have more than we need to live a comfortable life. The money spent on that excess could instead be used to save someone’s life, and should be.

As Australians near the end of the financial year, eyes wander to sales and minds flicker to the subject of tax deductions. June is traditionally a time when many make charitable donations. But how has the way we give – and think about giving – changed, and how can we do it better?

In the years since Singer’s book was first released there has been good news. Extreme poverty has declined and the number of children dying before they reach the age of five has reduced sharply. Lives have been saved by, among other things, the giving of money that those in the wealthy world do not really need.

Peter Singer: I want to shame charities into proving the worth of their spendingRead more

“Unfortunately, Covid may have stopped that decline [in child mortality],” Singer says. “But it does show we can actually make a big difference.”

Leading up to the bushfires of 2019/20 and Covid-19, charitable giving in Australia was marked by two trends: the amount donated rose substantially in the 2019 reporting year, by $1.3bn to $11.8bn. But the number of people doing the giving declined.

The decline in giving rates, suggests Elizabeth Cham, University of Technology Sydney associate fellow and former national director of Philanthropy Australia, could be related to wage stagnation. It is unlikely related to trust in charities, she argues, which has remained relatively high.

Krystian Seibert, charities and philanthropy expert at Swinburne’s Centre for Social Impact, says anecdotally Australian charities reported a mixed financial bag, but overall the picture appears more positive than many feared at the beginning of the pandemic.

Singer says Covid-19 presented an opportunity to see the world as smaller: “The sense that there’s only one world and we’re all in this together, I think, was strengthened.” However, that feeling has not translated into concrete outcomes. “If you look at the amount of vaccine that’s going to low-income countries, that’s very disappointing. It doesn’t show there’s any fundamental shift in saying: ‘Yes we are all in this together so we need to really do something.’ ”

However, he argues, we can do something, and so must.

“The wealth of many people [in Australia] has gone up quite considerably, and with that their capacity to give,” Seibert agrees.

In recent years, there has been a rise in nontraditional forms of philanthropy – reparations to wronged communities; mutual aid networks in response to Covid-19; and direct cash gifts to individuals and communities in need. There is evidence to suggest that direct donations in particular, are a highly effective method of giving, say Singer and Seibert But these acts don’t necessarily circumvent charities, which Singer argues remain necessary to provide administration and accountability for individuals’ gifts.

Effective altruism, as spearheaded by Singer, has gained in prominence since The Life You Can Save. The argument goes that not only do those living in relative comfort have an ethical obligation to give, but that there should be an emphasis on the biggest impact for that giving dollar. This lends itself to giving to extreme poverty alleviation and charities whose impact is quantifiable.

Acknowledging the impact the climate crisis will have on people, the environment and animals, Singer says the organisation which bears his book’s name is now working out ways to assess and recommend charities working in climate change.

But while Singer advocates for rational and effective philanthropy, he says there is another – scientifically-proven – reason for giving: it feels good.

“If people think about what’s important to them … they will realise it is important to think their lives have a larger purpose beyond themselves, and that it’s immensely satisfying.”

How to give effectively

Peter Singer: ‘Find the right charities’

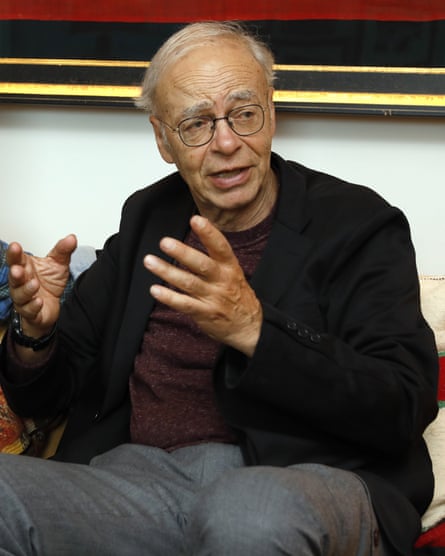

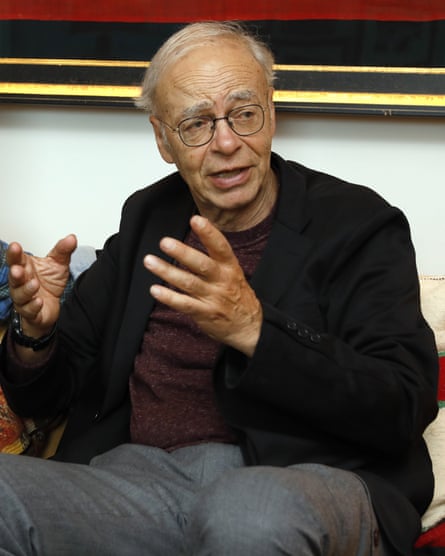

View image in fullscreenPhilosopher Peter Singer says Covid has strengthened the sense that ‘we’re all in this together’. Photograph: Richard Drew/AP

View image in fullscreenPhilosopher Peter Singer says Covid has strengthened the sense that ‘we’re all in this together’. Photograph: Richard Drew/AP

“The evidence is that most people don’t do much web searching or research before giving. We’d like people to think more about that and find the right charities to give to,” says Singer. That research and circumspection is only valuable, he says, if it leads to action.

The Life You Can Save’s Australian website lists 20 charities working to alleviate extreme poverty, which the organisation has assessed as being effective and providing good value for donors.

“We do that because we think that’s an important need, and it’s a way of making sure that your money goes very far.”

Krystian Seibert: ‘Do a bit of due diligence’

Seibert believes it is best to reflect on your personal values and aims when giving. “It’s not like you have to sit down and type it out – you can think about it while you’re driving or in the shower,” he says.

Once you’ve decided on a cause, “think about the types of organisations that are out there and do a bit of due diligence”. He suggests researching multiple charities in the same field online, looking at annual reports, and calling charities for more information.

Why are we so uncharitable to those doing good deeds?Read more

How that charity measures their effectiveness is key. “It may not be how effective altruism measures effectiveness, but any charity needs to be looking at how it’s doing and how it could improve.”

Elizabeth Cham: ‘Some of it will be used in very mundane ways’

When looking for information about a charity, says Cham, many people can be distracted by administration costs. Running an effective organisation takes resources, she says, and spending on administration in charities is as necessary as it is in any other operation.

“When you give that gift – your $50 or $100 – once it goes to charity and you get your tax deduction, [the charity] might use it to sweep the front step. Now, the front step needs to be swept,” she says. “Some of it will be used in very mundane ways.

“You won’t be saving lives. It will be used for what needs to be done.”